Opening hours

Mon-Sat 12am-6pm, Sun 10am-4pm

Late Night Art: 12am-9pm

printed politics

Production, posters, workshops. Part of Polish Cultural Week 2011

Spart Collective, Andrzej Zielinski and Vacuum

Ends 17 May 2009

This project shows original posters and pamphlets from the Solidarnosc movement in the 1980’s. Beyond their political appeal, these prints are minimal in their graphical composition and radical in the use of word and image.

This small retrospective of an underground movement and their outstanding graphic design will also update and re-activate the production of political posters and newsletters with the help of the art collectives SPART and THE VACUUM

With the assistance of the Polish printer Andrzej Zielinski, who printed political posters since the early Solidarnosc movement, 'printed politics' will give artists and activists the chance, to add and continue a printing tradition with a very simple silkscreen printing press, used for many underground publications.

For more information of the Polish Cultural week see.

LATE NIGHT ART and OPEN SUNDAYS is funded by Belfast City Council.

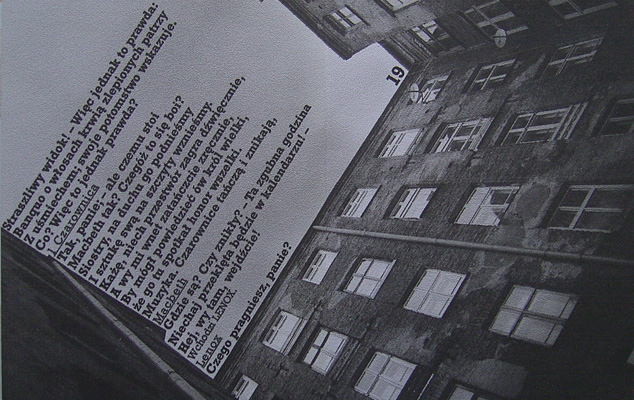

Installation view

Workshop

How we managed to topple communism with the help of knicker elastic

Text: Mirosław Chodecki

Poland has a very long tradition of fighting for the freedom of speech.

It had all begun in the 19th century during the time of partitions. Poland’s most eminent poets would publish their works outside their country. A hundred years ago, Józef Piłsudski, Poland’s latter commander in chief, was editing and publishing an underground periodical called “Robotnik” (The Labourer).

At the time of the German occupation in 1944, there were 603 underground press titles released, yet one could be sentenced to death if found involved in the process.

Communism however managed to close down the entire independent publishing movement. Although there were 22 magazines and 9 books issued in 1947, this dropped to just 3 magazines by 1952, disappearing entirely in 1954.

This situation lasted until 1968, when flyers first appeared due to student’s protests, this in turn was used by the communist regime as an opportunity for an anti-semitic hunt.

The genuine publishing movement came to life in 1976, the year the Workers’ Defence Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników) was founded.

This was also the time, when the Independent Publishing House, (Niezależna Oficyna Wydawnicza) of which I had the honour to be the coordinator, was established.

Why were there so many independent underground distributors arising?

Well, simply due to censorship's’ rage. There are thousands of cases of censorship interference. They were applied when discussing certain issues (ie. asbestos in Polish schools, meat export, accidents in coal mines, alcohol consumption etc.), and led to the ban on publishing particular authors (lists of those names changed continuously and they would extend in number rather than shorten). They also involved specific guidelines, ie.one could write a review on Leszek Kołakowski works but only in specialists papers and in a solely critical manner.

We know about it all only because one of the young censors – Tomasz Strzyżewski, who brought some of his notes and minutes while working for few months in Cracow`s censorship department. In comparison, not one of the huge tomes containing censorship records were found after Communism came to an end sixteen years ago.

At the end of the 1970`s, we had several magazines issued and by the time Solidarity was born, over one hundred books have been published.

The Independent Publishing House had the honour to release the works of several

Nobel Prize laureates even before they had been acknowledged through the award, ie:

Russian poet Josif Brodski, Czech poet Jaroslav Seifert, Jewish Yiddish language writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, Polish poets Wisława Szymborska and Czesław Miłosz, German writer Günter Grass.

I have a very peculiar story about Günter Grass, the Nobel Prize laureate in 2000.

I worked in the official publishing department for nearly ten years when his ‘The Tin Drum’ had been published. Some necessary changes were requested on a regular basis. Sometimes it was an indention about The Red Army and how it burned down the Old Town in Gdańsk; other times it occurred that a Soviet soldier would never have raped a woman. Grass never opposed it as time went on. And so the censorship would always find something new that required alteration. For two years I had been negotiating with Grass and his agents the issue of an underground release. Yet he was always hoping for the official edition – greater circulation, promotion in slick magazines etc. It was while Volker Schlöndorff was shooting a movie based on ‘The Tin Drum’, when Grass visited Poland. We met at that time.

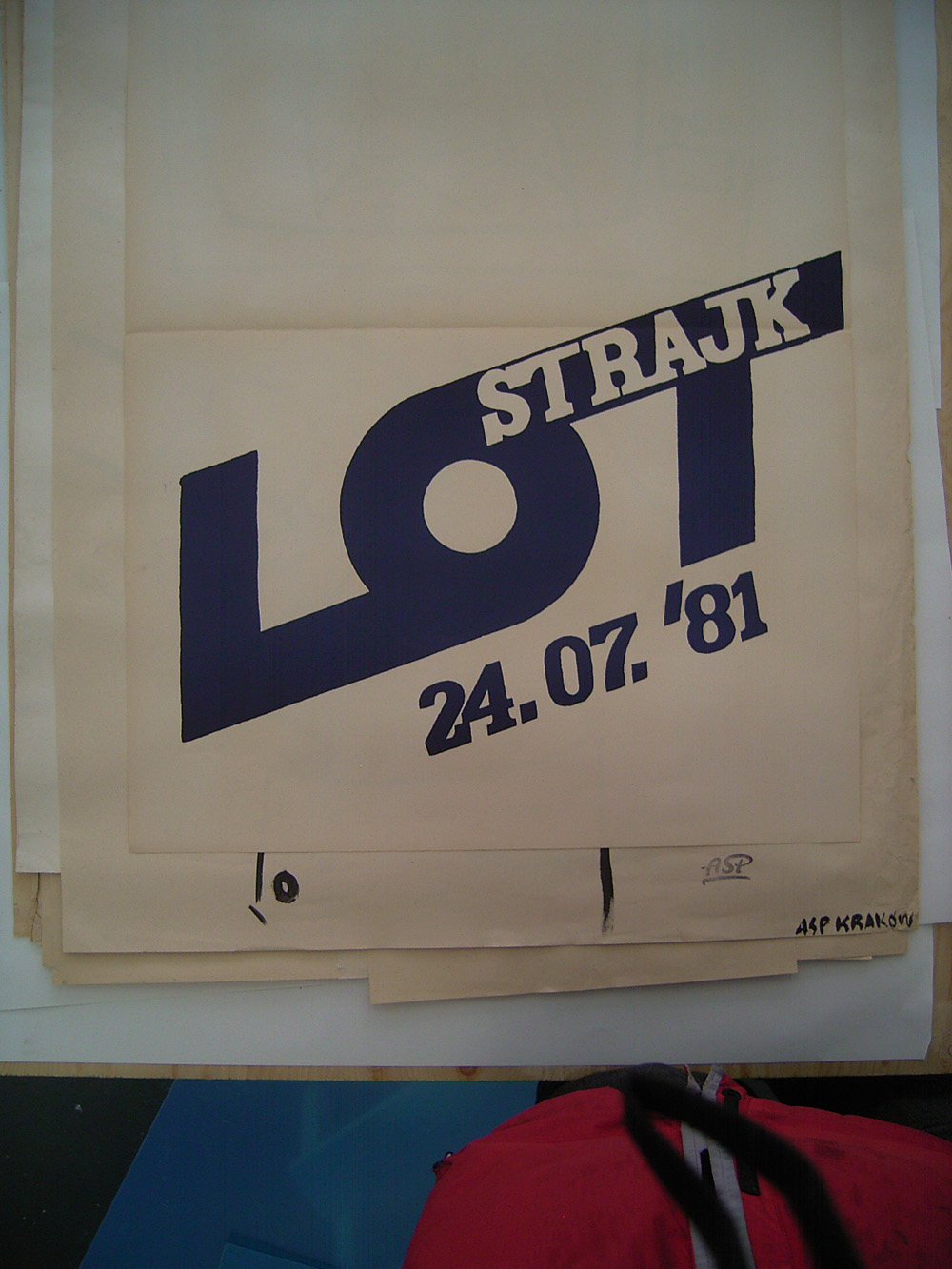

Elasic band printer

We went for a long walk along the rebuilt Old Town of Gdańsk. He mentioned the censorship`s proposal. In one of the scenes is a soviet soldier with a louse on his collar. The censorship recommended to remove the louse.

Günter - I said to him, this is not about the louse.

I have never read a more striking description of the defence of The Polish Post Office in Gdańsk in1939 than the one in ‘The Tin Drum’. This is a book that takes up a challenge of building new relationships between Poles and Germans, a novel that aims for a new covenant between our two nations. That is why it cannot be published in Poland. The only justification for the Soviet presence in Poland is the supposed danger coming from Germany. Russians are the ones, according to propaganda, who guard us against German revenge seekers. There are no good Germans in the official propaganda, hence your book will never see daylight in Poland. I somehow managed to convince him.

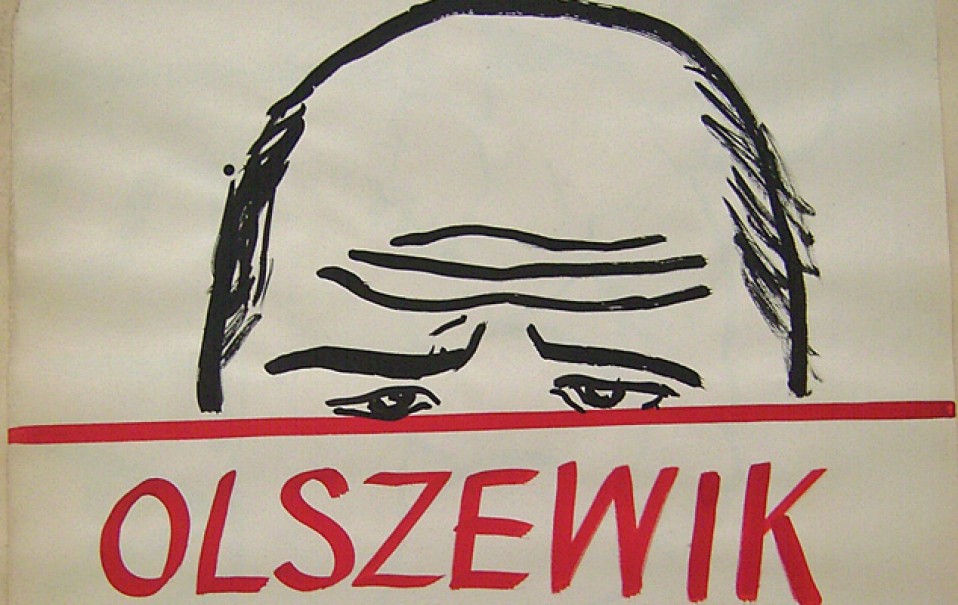

Poster

How come, in the country that tried to take control of everything and everybody, there was a publishing house, that could release roughly every other week a new book in a few hundreds and later in a few thousands copies?

We had a sufficient amount of paper brought to the place designated for printing. For example – to print Josif Brodski ‘Poem Anthology’ in the volume of 100 pages and in 3000 copies, there was 150 paper reams, around 400 kg needed.

Where did we get paper from? Consider that at those times in Poland everything was controlled and regulated. Common people would get stamps to buy flour, sugar, cigarettes, vodka, shoes etc. However, none of the socialistic organizations had a major problem with supplies. All it took was to counterfeit a stamp of the official Socialist Youth Association, and then, with appropriate documents, one could buy few tons of paper which would be stored for few weeks.

Next, we would bring a manual printing press. Where did we get it from? We were getting a lot of help from Polish emigration organizations. The Polish Government in London, Giedroyć and Parisian “Culture”, the Polish American Congress had all donated money and some good- willed people would smuggle devices into Poland.

After that, printers would arrive to designated locations with prepared stencils.

Their rota was split into three shifts - two printers would work at the same time and one would sleep. They would not leave the place until the print had been finished.

After the work was done, we would take the printing press to another place, where paper would have already been prepared.

Loose pressed pages would be brought to the so called binderies. One bindery would receive around 500 loose pages to be put together. In this particular case, the circulation had been divided into 6 parts.

The average binary was located in a small flat in a block, where a young couple would manually put pages together into a book after first putting their small children to bed.

Finished books were dispatched to various storage places and then collected by distributors. Each storage, which mainly used to be a small basement, was left with no more than 100 copies. It meant that the whole of Brodski anthology circulation had been divided into 30 parts before it reached the reader.

Obviously, the Political Police did not remain idle. By all means they were trying to solve the puzzle. The Institute of National Remembrance, that inherited the Political Police archives, handed over 4,000 pages of documents to me, with my name on them. These documents include only four years between 1976 to 1980. It works out that almost three pages a day were being created only about me. And at the time of late 70`s there were dozens of people like me.

Over the course of those four years I had been arrested and kept in custody for shorter or longer periods nearly 44 times. I would spend on average one day a week in prison. And with each apprehension the question arouse: is it for 2 days, 2 years or maybe 10? Such were the verdicts announced in Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union for far more insignificant ‘offenses’.

During the time of the Martial Law in Poland, after Solidarity had been de-legalized and banned and nearly ten thousand people taken into custody, there were at least 2700 magazines published, many for several years:

in Cracow “Hutnik”- 8 years

in Lublin “Informator NSZZ S”- 9 years

in Szczecin “Jendość” – 8 years

“Krytyka”- 13 years

in Poznań “ Obserwator Wielkopolski”- 9 years

student magazine from Cracow „Promieniści”- 8 years

“Solidarność” Białystok- 10 years, “Solidarity” in Gdańsk – 229 issues, “Solidarność Walcząca”-9 years 237 issues „Informator Toruński” – 8 years and 242 issues

„Tygodnik Mazowsze” – 8 years, 290 issues

„Z dnia na dzień”- 10 years, 524 issues.

One may ask – what has the knickers elastic to do with that? Well, it has indeed more to do than anybody may think.

The simple fact, that in those days in Poland anybody in his own flat could make prints and copies, is because of knicker elastic and to Witold Łuczywo. He created a new type of manual copying machine. All we needed was a picture frame and a stretched cloth. One had to place a stencil in it, paint it with a roller and the copy was ready. But at this stage, two people were needed, one was covering the stencil with paint, the other had to lift the frame and remove the copy. One day- for some unknown reason- the other person had not turned up. Witek was left on his own with some urgent papers to copy. His own genius told him to take his trousers off, to take the elastic from his knickers and to tie it to the frame. The other end of the elastic became attached to a chandelier, that was swinging over the table.

This was the moment, when the AUTOMATIC copier was born. The frame would pop up by itself. Later there was a plinth with the elastics fixed to the base of the frame. Such a device could be easily handled by one person. The best ones could produce around 1500 copies per hour.

The slogans ‘copy machines in every house’; ‘anyone can write, print and distribute whatever they want’ could do nothing but topple the communist regime with their destructive aim to gain complete control over its people and their thoughts.