Opening hours

Tues- Fri 11am- 4pm, Sat 11am- 3pm + 03. March Late Night Art 6-9pm

Open embroidery workshops

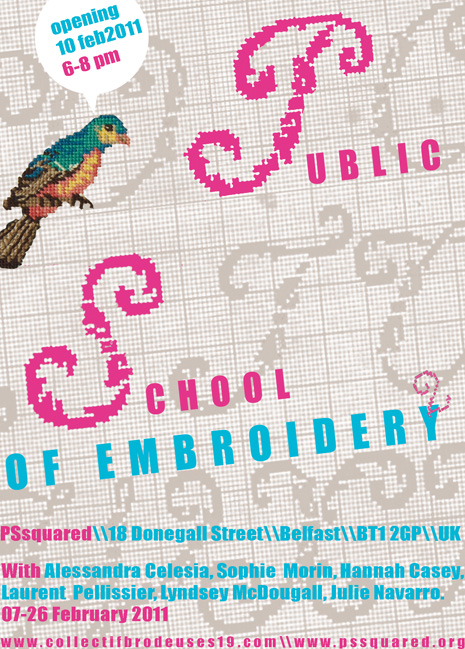

The public school of embroidery

Alessandra Celesia, Sophie Morin, Grazyna Areny, Julie Navarro, Laurent Pellissier, Javiera Hiault-Echeverria, Carlota Lohidoy in associacion with Hannah Casey and Lyndsey McDougall

Ends 26 February 2011

Open embroidery workshops, free for all interested and for all stages of perfection or imperfection

11 February

Friday

11am- 2pm

12 February

Saturday

11am- 2pm

15 February

Tuesday

10am-1pm

17 February

Thursday

6-9pm

22 February

Tuesday

10am-1pm

24 February

Thursday

6-9pm

Contemporary art is less strict with boundaries: what is art, what is craft, what is a hobby or happening? It is the creative potential and its social context what makes it interesting.

The 'collectif brodeuses 19', a Paris based embroidery collective is not a professional craft organization, but a loose group of people with different professional backgrounds and a common interest in needle craft.

They meet once a week in a coffee bar or at the 104 art centre and work on their piece of embroidery, stitch collectively on a single fabric, chat and exchange ideas. The old, domestic craft of embroidery used as a public social event and as a creative form of self expression, patience, skill and joy.

'The public school of embroidery' documents the initiative of 'collectif brodeuses 19' with its multidisciplinary approach, social mix, cultural understanding and embroidered work. Following this collective sense, local crafts people, artists and hobbyists working in embroidery are invited, to meet in informal workshops. These sessions are free and open to all, with or without skill and knowledge of cross-button-hole or running stitch.

It is a project about the technique and craft of embroidery, its traditional and contemporary practice and the social context of its non industrial production.

Links to artists using embroidery in their practice

Hannah Casey

Lynsey McDougall http://www.acompleteencyclopediaofthings.com/

Niamh White

Deidre Nelson

Amy Twigger-Holroyd

Northern Ireland Embroidery Guild

Workshop: spider

Exhibition of embroidery work by the 'collectif brodeuses 19' in a laundrette, Paris

Embroidery Goes Contemporary

Fredérique Joseph- Lowery

Such is contemporary art: computers are everywhere, and so what happens next? Embroidery makes a comeback. But then, as some of the examples here prove, needle and pixel can make deft partners.

A number of recent exhibitions in New York have highlighted the importance of embroidery on the contemporary art scene. Pricked: Extreme Embroidery, at the Museum of Arts and Design, offered an extensive panorama in which forty artists from a variety of cultural and artistic backgrounds and of both sexes set out to freshen up their subject.(1) Since the 1960s and 70s, embroidery has ceased to be a female preserve, a point eloquently made if we compare its rarity in the big P.S. 1 show Wack. Art and The Feminist Revolution and relative prominence in the 2008 Armory Show and in Volta.There, the Laurent Godin gallery presented the work of Corinne Marchetti, depicting an unkempt Catherine Deneuve, using black thread as if it were charcoal. At Yvon Lambert Francesco Vezzoli showed a jovial Hillary Clinton painted on a tapestry canvas shedding contradictory embroidered tears the same color as the cat’s eyes (Hillary and Socks Clinton). A more abstract piece by Isabelle Nolan, The Unfolding Moment (2007, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin), was laid on the floor, its dimensions open. Chicago’s Rhona Hoffman Gallery had AnneWilson’s Portable City, a minimal elevation of a city and its surrounds formed by thread stretched around small pins, for which she invented stitches unheard of in any embroidery manual. And here I am deliberately leaving aside all those works which used sewing patterns or rags of all kinds to create soft sculptures in order to concentrate on those works that problematize embroidery and interrogate the history of painting, photography and lithography.

Embroidery and art history

It was only in the Renaissance, when the hierarchy of the arts ranked needlework as a craft, that embroidery and painting went their separate ways. During this same period, a prohibition kept women from working in painters’ studios and the division of tasks ordained that men conceived the patterns while women followed their lines with measured stitches. The education of the perfect homemaker consisted in embroidering

sheets or cloths for trousseaus and covering and smothering each item of furniture (beds, tables, chairs, curtains, etc.).

Elaine Reichek (2), an artist who frequently evokes the political role of embroidery, lays bare its mechanisms. Rather than small sewn squares of fabric showing off her manual skill and consummate domesticity, her “samplers,” as she calls them, feature hand-embroidered quotations from Freud (on the theme of embroidery and masturbation) and the Brontë Sisters, who railed against the tedium of that activity or

perhaps the sexual arousal occasioned in visitors by the sight of a woman embroidering. All these situations and quotations are in fact discussed in Rozsika Parker’s seminal book, The Subversive Stitch,(3) which Reichek quotes from copiously. Parker’s epigram, “To know the history of embroidery is to know the history of women,” clearly indicates the magnitude of her subject. Reichek not only reminds us of this history, but she also corrects its development, invoking the history of art and gathering together her male predecessors in a sample book contained in a valise, just like Duchamp’s. Her spring and winter collection, Collection for Collectors, features samples of modern and contemporary art (Matisse, Mondrian, Magritte, Philip Guston, Ellen Gallagher, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Nancy Spero, Damien Hirst, etc.), all uniformly reduced to the same format of little embroidered squares cut with pinking shears. For Pricked, she made a more daring journey back in time to select samples from famous cloudscapes (Whistler, El Greco, Poussin, Morse,Turner, Richter) found on Google.The images were scanned and then encoded by a software that transforms pixels into stitches, thus revisiting the traditional role of embroidery as a way of passing on knowledge.The title of the work, too, is suitably encyclopedic: Lexicon of Clouds.The colored manufactured thread reproduces the hues of the masters, which, on another level, puts this work in the reverse readymade category.

The sewing machine fitted with a computer is more than a simple workhorse; it can now reproduce images. Endowed with more than foot and needle, it backs up the artist’s eye. Angelo Filomeno, who usually works with a rudimentary sewing machine, but who can still produce an inimitable zigzag stitch, like a painter’s

touch, uses new technologies to reproduce two embroidered skulls, Red Skull and Black Skull, presented as reciprocal negatives. Death thus looks at itself from both sides of the mirror and sees double. Here, technology is not meant to sing the virtues of progress but, on the contrary, to paint a needlework vanitas. Still lifes and skeletons performing danse macabres—the main medieval themes are present, with a Sadean

touch (Christ with a Whip) and highlighted by shantung silk, black precious stones and crystal, giving rise to sumptuous and precious embroideries that catch the light as no print could ever do. These works were exhibited at Galerie Lelong last March.(4) Among them, As the Lilies Among Thorns, So We Fall Like Love is a meditation on the Dürer print, Coat of Arms With a Skull (1503).

Among other pictorial traditions invoked, and not to be overlooked, is Pop Art: Mark Newport embroiders comics, Mattia Bonetti has made a couch sporting images from Chinese magazines in needlepoint, and Sonya Clark reproduces the greenback, kitting out President Lincoln with an Afro hairdo in lockstitch (Afro Abe II). However, the most prominent of these artists using embroidery is Ghada Amer, who in 2008 had a

retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum.(5)There the tiny stitches and deliberately slack threads of her work covered pornographic images from Hustler Magazine as well as Disney’s Sleeping Beauty. These hybrid works are like palimpsests in which Pop Art is covered with Abstract Expressionist drip painting. The collage of vigorously mixed threads calls for the same dynamism. The intent is political. The artist says that she deliberately subverts the virile affirmations of Expressionism and inveighs against her male teachers at Villa Arson in Nice, who forbade her to paint.(6) In the same spirit, her embroidered canvas The New Albers (2002) transports formalist abstraction into a formalist and pornographic figurative context. As she explains, “The history of art has been written by men, in practice and theory [...]. It became the major expression of

masculinity, especially through abstraction [...]. I occupy this territory aesthetically and politically because I create materially abstract paintings, but I integrate in the male field a feminine universe: that of sewing and embroidery.”(7)

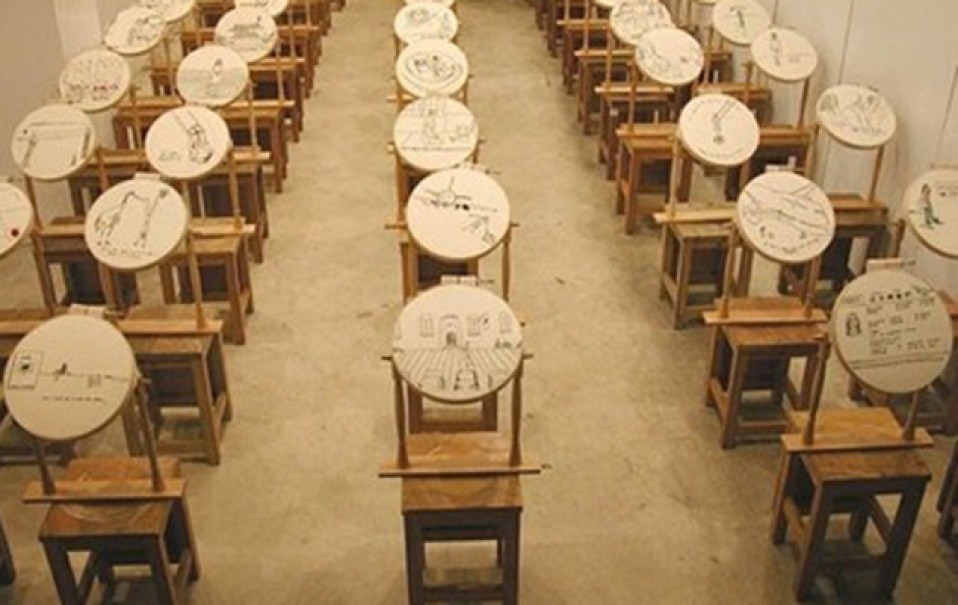

Installation view: The public school of embroidery

Workshop- Friday11February

Embroidery and photography

Extensively used, photography radically changes the world of embroidery, giving it an unprecedented realistic quality that it has never had before and heightens the impression of depth. Last May, at the Tilton gallery, Berendt Strik exhibited photographs taken in Africa in which large areas of luminous thread heightened the areas of shadow and light, while other parts were left untouched. Only thread could create the subtle shades of gray in the firmament of her Sky House. Tembo and Spotted Horizon exhibit an accumulation of chairs and tables laid out on a sophisticated grid that the subtle use of thread endows with a powerful 3D effect. At the Solo Impression studio, which does the embroidery for works by Filomelo, Reichek and Louise Bourgeois (Ode to Forgetting), Jean Shin showed five panels reproducing in black and white, and with highly visible pixels, fabric grooved by folds running in a variety of directions.(8) These pieces of fabric which end in musical scores stage big silver zigzags tracing the rhythms of music and sewing

machines. The fixity of these panels is offset only by the shimmering of their threads, but their seriality injects dynamism at the same time as they invite us to focus on the simple act of embroidering: And We Move (Pause).

Paddy Hartley stitches in, and with, time. He is the director of Project Façade, which is an artistic response to the Gillies Archive at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup (England). Sir Harold Delf Gillies was the first surgeon to have used photographs and artists to document his work “rebuilding” the faces of English and French

soldiers who were badly mutilated or burned in the FirstWorldWar—a Charcot of disfiguration, you might say. Hartley makes his embroideries on period uniforms, which he presents on dummies with featureless heads. The deformed head of one Lieutenant Spreckley, for example, is displaced onto pocket flaps, while embroidered drawings bear witness to the phases of the surgical rebuilding of his nose (blown off by a grenade), carried out over a period of four to five years. The braiding and other sartorial signs indicating wounds and grades are enriched by text recounting the officer’s personal history. Gillies’ notes and letters of support, including photographs, sent to the soldier from family and friends, are digitally embroidered with great precision onto the uniform.

John Clancy, Alessandra Celesia

Web archive image

Embroidery that is not pretty

Hartley’s work challenges the traditional decorative connotations of embroidery and endows it with greater substance. It makes abundant use of historical photographs, showing the horrors of mutilation. This world stands in violent contrast to the traditional motifs and feminine world of embroidery. Less violently, but in the same spirit, a number of artists are deliberately going against the assumed decorativeness of needle an thread. Annet Couwenberg, for example, models her doilies on the structures of viruses. One thinks here of a precursor, José Leonilson, an AIDS victim who in 1989 started making works evoking the disease of the blood using big red and black stitches. Needlework, which Louise Bourgeois described as “reparatory,” is not

as salutary as all that. According to Bourgeois, her mother restored antique tapestries, but in fact she was much more than a modest petite main: she also designed and made collages out of the fragments in her collection, (10) producing books that were a mixture of angels’ genitalia snipped from tapestries during the Reformation. It is, then, not at all surprising that Bourgeois’s own rag sculptures, with their deliberately

clumsy stitching, should have knives or guillotines hanging over them. Or that some of the heads that featured in her recent retrospective suggest comparisons with Frankenstein. In the same spirit, Morwenna Catt’s Phrenology presents a pretty raw portrait of a family of similarly patched-up heads. Where Paddy Hartley subversively explores the world of the military, Christa Maiwald stitches the heads of world leaders and dictators (GeorgeW. Bush stands next to Saddam Hussein) on young girls’ dresses in thin cotton that she places over lamps like shades.

Embroidery, a woman’s thing

In eighteenth-century literature the figure of the woman embroidering represents a paragon of virtue or, on the contrary, of sexual provocation—concentrating on her work, exposed to the male gaze. Both these idealized visions of femininity are attacked by Elaine Reichek in The Pounds.(11) This work reproduces a dialogue between Ezra Pound and Dorothy Shakespear, in which the poet chides his fiancée for

embroidering, an activity he placed no higher than smoking hashish, and argues that she should paint instead. This work, which appears to merely passively record the exchange, and comes complete with a photograph of the couple and a little hemp leaf for decoration, is actually both anachronous and subversive. Dorothy’s texts are reproduced in a font called “Cézanne” and Ezra’s in “Whitechapel,” derived from the

handwriting of Jack the Ripper.

To attack embroidery is an act of sexual violence. It calls into question women’s pleasure in embroidering, and the fact that they are not engaging in a “task” that calls for “energy” and “concentration. ”Woman’s pleasure in needlework is something intellectuals find intolerable. But artists are beginning to rediscover this libido which has been domesticated for so long. For Corinne Marchetti, embroidery is the ideal medium for relating sex stories gathered at openings or on movie sets, which she does in a personal diary drawn in a straightforward comic book style. Orly Cogan sews provocative vamps onto embroidered fabrics bought on the flea market, placing their sexual amusements within the little flowers stitched on by others. In Animal Farm, the silhouette of a Playboy Bunny is giving head to an embroidered blue rabbit. Birds of a Feather shows a cockerel on the shoulder of a man whose “bird” is surrounded by other feathered creatures in a faux naïve style. The sexual element is more discreet in a work by David Willburn, where a declaration of love sets up a simple embroidered setting—a sketchy barbecue or sink—which looks as if it has been just been drawn: I’m almost ashamed to say that you really are everything to me (2007) and I made this small ndrawing for you because I love you so fucking much. Number Two (2007). Andrea Dezsö embroiders her mother’s superstitions and her own sexual ups and downs: My mother claimed my sister was a rubber accident. As for Nava Lubelski, she brushes such matters aside and embroiders a tablecloth with a big splash, delighting in the pleasure of defying the rules of the game.

The world of contemporary embroidery is extensive and the issues at stake are considerable. And since embroidery is an art of edges—the edge of wounds, of sexuality, flourished or deflowered, an art of overflowing the genres established by art history, I shall conclude by remaining on the edge of works that I do not have time to evoke here, and that trace political or linguistic frontiers. For example, the one in which Ana de la Cueva presents an embroidered map and, alongside it, the foot of a sewing machine in the process of stitching a red line where the United States plans to build a wall to keep out illegal Mexican immigrants. Dafna Kafferman talks about the conflict between Israel and Palestine by embroidering handkerchiefs: Arabic is not spoken here. In Brooklyn, Ghada Ahmer delights in the fact that the words peace, love, safety and freedom exist in her mother tongue, Arabic, and sets out to embroider them one by one,(12) while, opposite, we are reminded that the word “terror” “is not indexed in Arabic dictionaries,”(13) and that it comes from the French Revolution.

Abandoning the world of peaceful interiors, embroidery has come to the museum to speak provocatively about our age’s most sensitive issues.

Translation, C. Penwarden

Frédérique

Joseph-Lowery is the author of two books on Salvador Dalí and is curating the exhibitions Ray Johnson, Andy Warhol and Salvador Dalí (Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, April 2009) and Dalí Dance (Godwin-Ternbach Museum, Queens

College, spring 2010).

(1) Curator: David Revere McFadden (Nov. 2007–April 2008)

(2) See in particular Elaine Reichek: At Home And in TheWorld, with an essay by Lynne Cooke, Société des Expositions du Palais

des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, 2001

(3) The Subversive Stitch. Embroidery and the Making of The Feminine, London:Women’s Press, 1984

(4) Angelo Filomelo, Betrayed Witches, March-April 2008, Lelong, NewYork

(5) Ghada Amer, Love Has No End, February-October 2008, organized by Maura Reilly

(6) See her talk at the Brooklyn Museum, spring 2008

(7) Published on the exhibition website under the title Feminist Artist Statement

(8) The fabric is an enlargement of a few inches of cloth from the conductor’s jacket in which he conducted a rehearsal of the

piece whose score is shown at the bottom of the image. The title of the work is one of his instructions. The embroidered line

simulates a photograph of the sound waves from the music, Ma Vlast by Smetana

(9) http://www.projectfacade.com

(10) On this subject, see Brigitte Cornand’s trilogy on Louise Bourgeois. On the specific use of needles in sculptures, see my

article “Louise Bourgeois: her need for needles,” to be published in Artnet magazine

(11)This piece has just been bought by MoMA

(12)The title of each canvas is given by the word embroidered on it (2008)

(13) The Reign of Terror, 2005.

Workshop, Friday, 11. February: Urban subjects

Contemporary Embroidery

When most people think of embroidery, they conjure up images of old ladies stitching tablecloths or department store kits depicting cute kittens. While there are in fact still a great many people who do kits, and even a few remaining tablecloth-makers - and good luck to them - modern embroidery has come a long way.

Under the guise of 'textile arts', contemporary embroidery covers a wide range of disciplines, and is rightly now considered an art rather than a craft. It can cover creative stitchery by hand or machine, and can use all sorts of materials, not just fabrics but also papers, wood, plastics and even metals.

Embroidery in the Past

Embroidery is an ancient art. Although textiles don't normally preserve well, needles often do, and what evidence there is suggests that people have been embellishing their clothing and their homes for as long as they've had them, with examples dating back not just centuries but millennia. A lot of the basic hand-stitching techniques have changed very little in all that time, and are fundamentally the same all over the world; what does differ is the way in which they are applied.

From being a high-status craft in the Middle Ages, often practised by men, by the 19th Century in England the work of professional embroiderers had been largely replaced by industrial processes and embroidery was reduced to being thought a suitable occupation for genteel ladies confined to the home with very little else to do. This remained the case for many years, until a renaissance of this ancient tradition in the mid-20th Century.

The Revival

The leading light in this revival was Constance Howard MBE. She became principal lecturer in textiles and embroidery at Goldsmith's College, London, in 1947 and in the years after that led the avant-garde movement in textile work, and encouraged many people outside the art world to experiment with design and their own creativity with a series of books. Her influence was, and is, enormous and led to all forms of textile arts being taken seriously and taught by colleges and universities, both in the UK and internationally. Many world-renowned artists work with textiles and stitchery: Paddy Killer, Barbara Lee Smith, and Michael Brennand-Wood to name but a few.

Today, embroidery is seen as a rich and varied art, with many materials and techniques available, both ancient and modern, and a strong emphasis on design. This has lead to a body of innovative work making wide use of texture, form and the sense of movement inherent in fabrics. This ancient art has never been stronger as it moves into the future.