Time

6pm

URBAN/ ACT

Presentation and talk of URBAN/ ACT - a handbook for creative urban actions.

Doina Petrescu, Fiona Woods

Ends 02 June 2008

Speakers: Doina Petrescu (aaa) and Fiona Woods (Ground Up)

Launch of a new handbook of contemporary urban practice from across Europe (tactical, situational and active) - considered in relation to ongoing work on creative rural practices in Ireland.

URBAN / ACT, edited by aaa (atelier d’architecture autogérée), Paris/2007 ISBN 978-2-9530751-0-6 is the outcome of a series of discussions and collaborations with a number of groups from France, Belgium, England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Holland, Spain, Croatia, Slovenia and Canada.

The practices presented include artist groups, media activists, cultural workers, software designers, architects, students, researchers, neighbourhood organisations, city dwellers. Most of these groups are usually catalogued as local and their position is minimalised as such, but in fact they are highly specific and have the quality of reinventing uses and practices in ways that traditional professional structures cannot afford (due to their generic functioning). Their ways of being local are complex and multilayered, involving participation and local expertise as well as extra-local collaborations. They reinvent contemporary urban practice as tactical, situational and active, based on soft professional and artistic skills and civic informal structures, which can adapt themselves to changing urban situations that are critical, reactive and creative enough to produce real change.

URBAN/ACT focuses mainly on groups in cities and their activities in a dense urban environment, representing a dominance and assumed monopoly of city culture. In the predominantly rural context of Ireland, does the urban act need to change its methods and strategies; does rural act mean a slower pace, from hard edge challenging to organic soft and comforting?

Fiona Woods will analyse examples of creative rural practice in Ireland and re-balance the city-centricity with a RURAL/ACT appendix.

Doina Petrescu is reader in architecture at the University of Sheffield. She has written, lectured and practised individually and collectively on issues of gender, technology, (geo)politics and poetics of space. Together with Constantin Petcou, she is founder member of atelier d’architecture autogérée (aaa) and has also been an activist with local associations in UK, France Romania and Senegal and feminist research groups such as association (des pas) in Paris and taking place in London. Editor of Altering Practices: Feminist Politics and Poetics of Space (London: Routledge, 2007) and co-editor of Architecture and Participation (London: Routledge, 2005). The aaa collective initiated and edited URBAN/ACT.

atelier d’architecture autogérée / studio of self-managed architecture (aaa) is a collective platform, which conducts actions and research concerning urban mutations and cultural, social and political emerging practices in the contemporary city. http://www.urbantactics.org

Fiona Woods is a visual artist; her practice includes curating and writing. For the last number of years her work has focused on questions of art and public space in non-metropolitan contexts. Recent commissions include Imagining Silvermines; a psychogeography (as visual-artist-in-residence for North Tipperary, 2007) and a collaborative R&D residency for Grizedale Arts, UK (ongoing). She devised and curated the Ground Up programme of public art in rural contexts for Clare Arts Office and co-devised the Shifting Ground partnership project between Clare Arts Office and GMIT. She is editor of the forthcoming publication Ground Up; re-positioning art in the context of the rural (2008).

Fiona Woods- talk

The non-metropolitan; a site of resistance

Text based on the talk given by Fiona Woods at PS²

“Half of the world’s population now lives in cities.” This is a statistic with which most people are familiar and is reflected in the growth of ‘urbanism’ within cultural studies. The methods by which cultural discourse is generated – through art journals, art colleges, curatorial practices, discursive events, funding agendas etc. – present the urban as the site where cultural innovation and resistance is most likely to occur.

Of course, there remains another half of the world’s population - people who don’t live in cities but in non-metropolitan contexts. In contrast to the discourse of urbanism, theirs is a marginal discourse, discontinuous and non-elite, often characterised as non-progressive, traditionalist, backward looking.

This essay will attempt to present a mobilisation of public space which is not urban, but nonetheless represents a reconfiguration of what Jacques Ranciere calls the ‘distribution of the sensible’ – that is, what can be seen, what can be thought and what can be talked about. I will endeavour to show that this space is as much a site of potential resistance as urban space, that here too cracks and slippages can be located wherein to consider and counteract hegemonic strategies.

In our present world, all contexts, urban and non-metropolitan are subject to a quintessential colonial strategy, the Oil Paradigm. This is an employment of superior technology and institutional mechanisms to impose one set of cultural, social and economic values on another for the purpose of extracting wealth to benefit an elite – but these days we call it corporatisation. Similar in many respects to what Hardt and Negri term Empire, it is a web of values centred on consumption, which prioritises the economic over the social, encourages the separation of production and consumption, preferably by a great distance, and imposes a ‘progressive’ temporality.

Public space is actually a spatio-temporal matrix, but while the spatial is much discussed the temporal is rarely held up to scrutiny. We inherited from the project of modernity an understanding of time as singular, forward-moving, always breaking with the past; this is what it means to be modern, and it is the basis of Capitalist time. The lens of unidirectional temporality creates a model of history as linear, generating some of the great, almost unquestionable modern myths such as ‘economic growth’ and ‘progress’. Following this model ideas, events, things become easily outdated which renders them obsolete, irrelevant.

Post-colonial studies have thrown up a different understanding of time in which multiple modernities exist and overlap in different places at different times. Subaltern studies in particular, with its emphasis on non-elite histories, has made evident the way in which non-elite social and cultural formations are occluded rather than erased or superseded by dominant social narratives, and how they persist in that occlusion.

When I use the term ‘non-metropolitan context’ I am not necessarily referring to a physical place but to that which lies outside of the dominant, metropolitan discourse and which can be described as alterior. Viewed through this other lens, the social and cultural forms characteristic of non-metropolitan contexts are contemporaneous with modernity, but displaced to the margins. This is significant because the great cliché surrounding the non-metropolitan is that it belongs somehow to the past, that it is irrelevant, reactionary, traditionalist, incapable of generating anything radical or resistant.

Climate change and peak oil require that we shift all modes of understanding and practices to adopt new, sustainable forms of living and being in the world, with an emphasis on the local and the translocal. Fluid City is a proposal by an Irish architect, Dominic Stevens for a vibrant, intensive linear settlement along the banks of the Shannon-Erne waterway in the West/ North-west of Ireland which has about 800km of usable shoreline. The flood-plains or callows as they are known are intended for use as farm land, worked sensitively with local systems of ecology; the houses are designed to rise and fall as the rivers swell and flood. A moving city can appear overnight; this is an ephemeral, adaptable resource – the city travels to the people instead of the other way around. So, the bank, post office and shop might come twice or three times a week, the cinema and bookshop could come once a week, while the National Gallery could come once or twice a year. In line with many of the houses that Stevens designs, these are intended to be built relatively cheaply, avoiding the need for huge mortgages. They are also designed so that they could be built by communities using the meitheal system of shared and bartered labour; community building is employed as a social and economic strategy. The population density would be in the region of 400 people per kilometer of shoreline, so it’s an intensive rather than exclusive use of land.

There are many interesting challenges to hegemonic strategies in this proposal. First of all, Stevens is thinking outside the model of Roads Culture that has come to dominate Ireland over the last 15 years. Since the Roman Empire roads have been a primary means of broadcasting colonial power; In Ireland today new roads are one of the primary means by , which ‘mortgage culture’ is broadcast. Mortgage culture is an extremely efficient means of population control; people with very high mortgages to pay can easily be frightened into voting for things that favour ‘economic growth’ if they vote at all; they are less likely to have time or energy to protest about social issues. In addition the values of the Oil Paradigm that I described earlier are achieved through a progressive de-localising of the economy and the culture, so people no longer cultivate food or eat local produce, fewer people work locally, the majority of people don't shop locally and so on and it becomes very self-perpetuating so that people come to depend increasingly upon roads and the kinds of economics that go along with them. Fluid City addresses many of these issues.

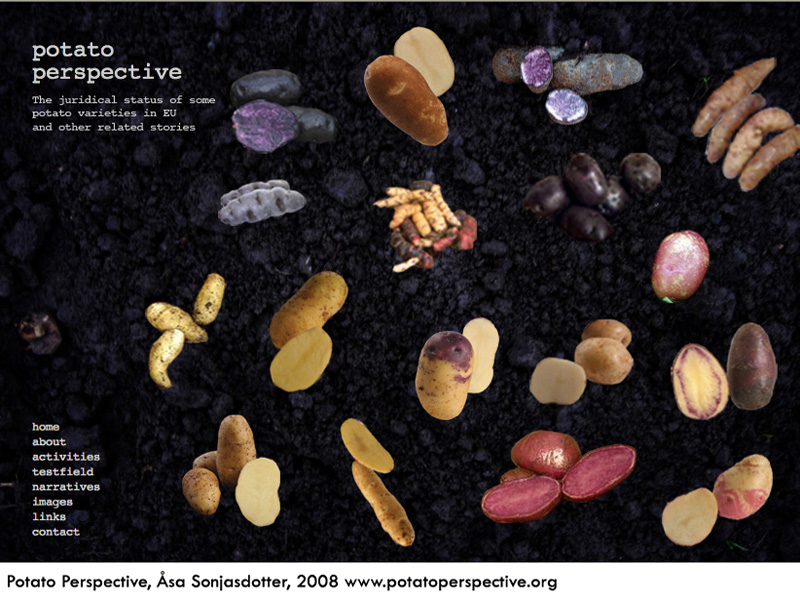

potato perspective

Returning to a discussion of space for the moment, the internet has given us cause to reconsider where we locate and how we understand public space, but in a way that is very compatible with a metropolitan discourse.

The Potato Perspective, a work presented on the web by Danish artist Asa Sonjasdotter, engages another kind of space which could be said to lie beyond the dominant cultural discourse.

The artist embarked on the project after spending time at the Navdanya centre, an organisation in Northern India that resists corporate control and exploitation of seed stock, by collecting, developing and sharing local varieties of rice, wheat and beans. On return to Denmark the artist wanted to transfer the experience to the Scandinavian cultural and environmental context and somewhat innocently selected the potato as a comparable staple within the Scandinavian diet. She collected some old species of potato and began to cultivate those, but in the process encountered the complex world of European Seed Law.

http://www.potatoperspective.org/narrativestart.html

When countries join the European Union, they must produce a National Varieties List; commercial producers then have an opportunity to register a variety for legal distribution, for which they pay a substantial annual fee. They can also apply for a Plant Breeders Rights or PBR certificate if they can show some minor modification to the variety, for which they can then claim royalties. Unregistered varieties cannot be grown commercially and where a registered PBR certificate holder ceases to maintain a variety it can lead to that variety being de-listed which then renders it illegal.

As such, within the context of the European Union the potato becomes a kind of public site where the intricate relationship between food regulation and privatisation is made apparent. This is much more than an agricultural issue; when regulatory powers enter into alliance with commercial interests it inevitably impacts on questions of autonomy and freedom. The appropriation of seed-stock and the like for private, economic gain is a matter of common political and cultural import.

The corporatisation of food production is undoubtedly a primary outcome and probably one of the primary motivations of agricultural regulation; I don’t think there is anyone who would contest that the WTO and GATT represent the interests of big business over small, indigenous farmers. The impact of this has also been felt in Ireland which has seen the systematic ending of farming and food production; in that process the nature of rural space has shifted from the concrete to the abstract, from a site of production to a site of consumption, from a place of self-sufficiency to a place of amenity provision.

In my own practice I am often trying to discern the ways in which rural space is ordered and controlled and to locate occluded or counter-hegemonic practices and thinking. The character of non-metropolitan space is quite different to that of urban space –topographically space tends to be more apparently open and horizontal but subject to an invisible architecture of regulation governing land-use; rural audiences or publics are more dispersed but often less transitory so encounters tend to be quite different; temporality is not linear and progressive as I described earlier but tends to include the past in a more real and concrete way; engagement with nature is integral to the social, economic and cultural matrix and then of course there are areas which are neither urban nor rural.

Silvermines: Becoming Utopia is a work in progress; it is the second stage of a project that I undertook last year as visual artist-in-residence for North Tipperary. I deliberately adopted an aesthetic framework borrowed from the Situationist International and called the first stage of the project Imagining Silvermines; a psychogeography. Drawing on situationist practices I made a decision to work with whatever was presented to me; I also wanted a clear and definite aesthetic framework for the project to avoid becoming overly identified with the language of social engagement, which is vulnerable to instrumentalisation as the management of public art practice in Ireland and in the UK in increasingly institutionalised and placed in the service of state interests.

Silvermines is an area of ecological disaster; seven centuries of mining have left the watercourses and the land impregnated with heavy metals. It is also a beautiful place with an incredibly interesting and complex history. Using the Space Shuttle I entered into an agreed exchange with the people of the village; I provided a space and a display service arranging whatever material people brought to form the ‘collection’ of a temporary museum, in response to a passion for local history that I encountered all over Tipperary but particularly in Silvermines. In return they afforded me an opportunity to enquire into the narrative constructions and practices that were used by different groupings within that community to make sense of their place, including nostalgia, racing and burning out cars, graffiti, farming practices, a kind of epic poem tradition peculiar to the area, and also an unpicking of the construction of local history.

In response to that first encounter stage and with the intention of extending the notion of psychogeography that informed it I am developing a publication for distribution back into the community that befriended me and vice versa; the intention is to reflect the ‘tactics’ employed by different groups of people to make sense of this place. The publication is also an attempt to place the project in critical relation to itself, to subvert conventions of ‘reading’ and include the participant-reader in the act of meaning making. To that end the publication will include a number of movable elements and sections, a number of board games designed around the realities of the place, a fictional ‘I’ve Been to Silvermines’ tourist merchandising line based on the legacy of mining for a much-desired but presently absent tourist industry, and a selection of material and maps gathered or generated through the project that may be real or fictional. The completion of the project is currently funding-dependant.

With all of the references that I have made to margins and the marginal, it’s probably appropriate to conclude with a work that considers a form of space which is literally marginal and beyond the mainstream.

BorderXing is a work by the artist Heath Bunting that has been carried out on and off over a number of years . He makes unauthorised crossings of borders between European countries in various locations, including forests, rivers, mountains and tunnels; he painstakingly documents the routes and makes a detailed record of all his movements.

These are available in the BorderXing Guide which is only available by making a direct application to the artist.

Since the 1980’s border art has developed as a genre that addresses international power relations, recognising that borders are not lines but symbolically charged zones of relation. I read Bunting’s work as an attempt to re-subjectivise these spaces in response to the way that liberty is increasingly sacrificed in favour of security. It’s also a Situationist project par excellence!

To conclude, the point is not to place the urban in opposition to the rural or the metropolitan to the non-metropolitan. There is much to be resisted in the face of “. . . a system of power so deep and complex that we can no longer determine specific difference or measure”. (1)

In order to locate the cracks and vacancies where such resistances might be practiced, all existing discourses including the metropolitan and the non-metropolitan need to be deconstructed for signs of hegemony. In urging a re-examination of that which lies beyond the dominant metropolitan discourse I do not advocate a ‘return’, to the past, to purity, to the formerly glorious or to anything else; what I urge is a ‘stepping outside of’ so that new forms, new hybrids, new discourses can be elaborated.

( 1) Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire Harvard University Press, 2000, pp 210 - 211